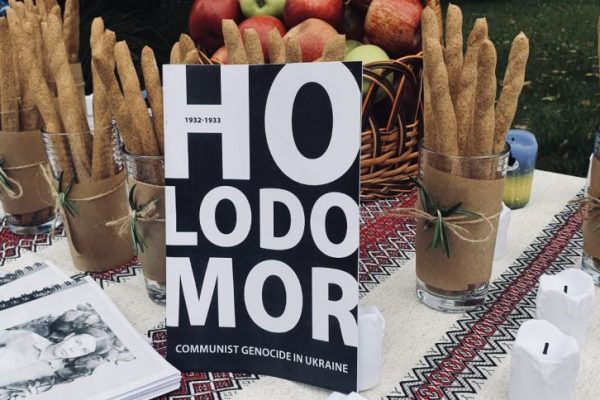

In 1929 the Soviet Union started the policy of forced collectivization. The peasants reacted with thousands of protests, unwilling to join the collective farms. To suppress the resistance and to ensure profit from the grain sales Joseph Stalin imposed on Ukraine a plan to extract 4,2 million tonnes of food, a plan that had to be “performed fully and unquestionably, at all costs”. Throughout the Holodomor, when people were dying from starvation, the Soviet Union continued to export grain. Meanwhile, all food that security forces could find in a household was taken from the peasants. They were not allowed to travel outside their villages to prevent them from finding food in other areas.

When the police came to confiscate all the food from Yulia’s grandmother’s family, they managed to dig an under-ground shelter under their building where they hid the cow. By scarcely using milk and collecting a mountain spinach to make flour their family managed to survive.

“My great-grandmother taught us to value bread and to the end of her days she would always carry a piece of bread in her pocket”.

When the idea of the bench came up, I decided to draw the tree of life – a symbol very commonly used on Ukrainian embroidered towels that represents the connection of different generations and their embeddedness in nature.

“Before the Holodomor the tree of Ukraine was flowering, but after the famine the fears of hunger changed people’s life and character for decades.”

Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959) who was born in Lviv, now Ukraine, and coined the term ‘genocide’, used Holodomor to explain the meaning of ‘genocide’.

However, for almost 70 years the Soviet Union denied Holodomor, and would prosecute those who would speak about it.